A SURVEY OF

CONFEDERATE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

QUARTERMASTER ISSUE JACKETS

by

Leslie D. Jensen

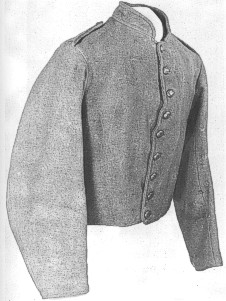

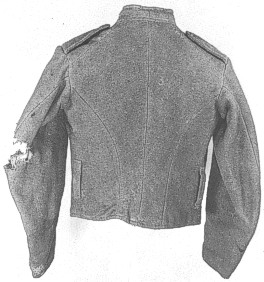

Type II Richmond jacket of Private John Blair

Royal, 1st Co., Richmond howitzers,

showing where a shell hit Royal in the left arm during the Battle of

Chancellorsville.

The study of American military uniforms has been pursued with increasing

sophistication over the past forty-odd years, with the result that today

we are light years ahead of our predecessors in nearly every period of our

history. One area, however, remains only sparsely covered, and often is so

dominated by the mythology of the past that the historical truth is

difficult to discern.

The question of what type of uniforms the Confederate States of America

issued to its troops has been of considerable interest for sometime, but

to date little concrete evidence has surfaced that would allow us to

differentiate between uniforms issued by the central government, those

issued by the states, private or foreign purchases, and home made items.

Despite some truly important work by members of the Company and others, we

still remain ignorant of much of the inner workings of the Confederacy's

supply system and clothing procurement practices.1

Perhaps, too, we are still too easily lulled by an appealing image of the

"ragged rebel," and therefore naively accept the concept of

Johnny Reb being supplied indefinitely by the folks at home, conveniently

ignoring the fact that no army, however resourceful, wages war very long

if it doesn't develop a workable supply system.

Part of the problem in this area has been that what work that has been

done, particularly by Company members, has concentrated on the distinctive

uniforms worn by particular units, almost always from early in the war.2

There are a number of good reasons for this. First, if any information on

a distinctive uniform exists, it is usually fairly easy to find in period

newspapers, letters, diaries or photographs. Second, the information is

usually specific enough to allow reconstruction of the uniform, and the

reconstruction conveniently fits a format such as Military Uniforms in

America. Finally, most of these early war uniforms were sufficiently

different from one another to illustrate unit distinctions and, therefore,

are fit subjects for a plate series.

This type of research is important and badly needed. It helps to fill gaps

in our knowledge and hopefully we will see even more of it in the future.

It has helped us to learn a great deal about the uniforms of southern

volunteers as they marched to war in 1861. What it has not done, however,

is to help us learn much very specific about what the majority of

Confederates were wearing for most of the conflict.

In

this latter area, we have instead developed a body of knowledge of what we

believe the "typical" Confederate looked like. The best of this

provides us only a rough outline, while much of it is often nothing more

than loose guesswork.3 There are a number of reasons why nothing more

concrete has been worked out to date.

First, the destruction, or at least the apparent destruction, of much of

the Confederacy's Quartermaster records at the end of the war was a heavy

blow to researchers. Compared to the

massive Federal records, what has survived is a pittance. At the same

time, much of what has survived has not been properly utilized. A great

deal of useful information still exists, but it is scattered, and it takes

dedicated work to retrieve it.

Second, research in this area has been affected by a school of thought

that contends that Confederate resources, across the board, were uniformly

inadequate to supply the army's needs, and that what Johnny Reb did

receive in the way of clothing came overwhelmingly from the home folks.

Obviously, in such a situation, there were no uniforms. Therefore, there's

no point in looking for them.

Certainly, this school of thought was spawned and influenced by post-war

Southern historical writing, much of which was directed towards justifying

the Confederacy's efforts. Out of this school came the emphasis on the

"ragged rebel." While certainly truthful at times, such as

during the Sharpsburg campaign, the "ragged rebel" came to

personify the Confederate soldier for the whole war. For southern

apologists, it was a perfect image. Not only was the "ragged

rebel" appealing as a staunch individualist fighting for his

independence despite a lack of almost everything with which to do it, he

also served as a plausible explanation for Confederate defeat. The more

ragged and lacking he was in basic equipment, the more glorious his

victories and the easier to accept his defeat. Other factors, such as

unequal heavy industry, railroads, armament production and naval power

were certainly far more powerful in their effects on the war effort than

the clothing on the soldier's back, but the "ragged rebel" stood

as a convenient symbol that has unfortunately obscured much of what the

Confederacy accomplished, and has even diverted attention from some of the

other things that went wrong." 4

Strangely enough, much of the legend-building was accomplished by a

limited number of individuals, many of them the sons and daughters of the

veterans.5 Most of the veterans themselves, in their reminiscences, never

addressed the problems of supply at all, and of those that did, a

surprising number challenged the prevailing view. As an example, W.W.

Blackford, who served on General J.E.B. Stuart's staff, noted:

"...In

books written since the war, it seems to be the thing to represent the

Confederate soldier as being in a chronic state of starvation and

nakedness. During the last year of the war this was partially true, but

previous to that time it was not any more than falls to the lot of all

soldiers in an active campaign. Thriftless men would get barefooted and

ragged and waste their rations to some extent anywhere, and thriftlessness

is found in armies as well as at home. When the men came to houses, the

tale of starvation, often told, was the surest way to succeed in

foraging... " 6

A

close look at contemporary Confederate records, including those for the

blackest period of the war, reveal some startling statistics. For example,

during the last six months of 1864 and including to 31 January 1865, the

Army of Northern Virginia alone was issued the following:

104,199

Jackets

140,570 Pairs of Trousers

167,862 Pairs of Shoes

157,727 Cotton Shirts

170,139 Pairs of Drawers

146,136 Pairs of Shoes

74,851 Blankets

27,011 Hats and Caps

21,063 Flannel Shirts

4,861 Overcoats

These

were field issues only, and did not include issues to men on furlough,

detailed at posts, paroled and exchanged prisoners or any other issues.

Moreover, these were overwhelmingly central government issues, and did

not include issues by any states except part of North Carolina's. During

this same period, Georgia provided to the Confederate Army as a whole,

over and above the figures quoted above:

26,795

Jackets

28,808 Pairs of Trousers

37,657 Pairs of Shoes

24,952 Shirts

24,168 Pairs of Drawers

23,024 Pairs of Socks

7,504 Blankets 7

At

this same time, field returns showed the Army of Northern Virginia with a

maximum strength of 66,533, including 4,297 officers. 8

Obviously, because

of personnel turnover, the actual number of people in the army was

somewhat

greater; but at the same time it is obvious that with the exception of

overcoats, hats and caps, and flannel shirts, many of which had already

been provided, the Army of Northern Virginia was not only well supplied,

but in some cases extravagantly so.

Moreover,

while the statistics quoted above are from the records of the

Quartermaster General, there is evidence that at troop unit level, the

material was being received and there was a perception of abundant

supplies. On 3 October 1864, a board of officers was convened in Corse's

Brigade, Pickett's Division, to examine a lot of 226 jean jackets to

determine whether they were fit for issue. If unfit, the jackets would

have been condemned and more requisitioned. This quantity would have

outfitted nearly a fourth of the brigade, and is highly doubtful that

experienced officers would have even considered condemnation of such a

large amount of clothing had it been difficult to obtain. Obviously, it

wasn't. 9

This same brigade announced in February, 1865 that officers could

buy shoes from the brigade quartermaster, ".. .the immediate wants of

the troops ...being supplied..." 10

Within

the Confederacy's other armies, the same basic story seems to hold true,

although some were not as well supplied as Lee's men. 11

Still, if

scarcity was in fact not a problem, it stands to reason that at least some

of this material ought to survive, and ought to be identifiable as

Quartermaster products. Indeed, it can be, but not before one has a thorough

understanding of the Confederate clothing procurement system.

The

Confederate Quartermaster's Department was organized by Act of Congress

26 February 1861. This act, along with one passed 6 March, established the

Confederate Regular Army, an organization with a paper strength of about

6,000 men. As finally organized, the Department was authorized one

Quartermaster General with the rank of colonel, an Assistant

Quartermaster General ranked as a lieutenant colonel, four Assistant

Quartermasters graded as majors, and as many Assistant Quartermasters (AQMs)

ranked as captains as the service might require. 12

At

the same time, a second series of acts established the Provisional Army of

the Confederate States (PACS) and authorized the President to accept up to

100,000 volunteers for 12 months to man it. 13

The Quartermaster's

Department, by law was responsible for clothing only the Regular Army. The

volunteers of the Provisional Army were to provide their own clothing, for

the use of which the government would pay each man equivalent of the cost

of clothing for an NCO or private in the Regular Army, generally $25.00

for each six months. This was the Commutation System. Initially it seems

to have been intended to provide a means of clothing the troops without

having to build government facilities to do it, to take advantage of the

easiest way to clothe the army, and to avoid the risk of stockpiling

mountains of material that might become useless surplus if there was no

war. 14

In

the meantime, however, there was the Regular Army to supply. In April,

1861, the Quartermaster General, Col. A.C. Myers, ordered Capt. John M.

Galt, AQM in New Orleans, to let contracts for 5,000 uniforms for Regular

Army recruits. These uniforms were to consist of a blue flannel shirt to

be worn as a blouse, steel gray woolen trousers, red or white flannel

shirts, plus drawers, socks, bootees, blankets and leather stocks. 15

Caps were added later. 16

On

24 May, Galt was sent a memo detailing the new regulation uniform that

became official 6 June, and which is well known through the published

uniform regulations. It is important to keep in mind that at this time

these were Regular Army regulations. He was told to receive propositions

from contractors for 10,000 suits of this new uniform and to advise the

Quartermaster General as to price and quantity that could be obtained in

New Orleans. 17

Before

he could respond, Galt received a flurry of correspondence from

Richmond. On 31 May he was told to have suits of gray made up as fast as

possible, and to let Myers know how fast clothing could be furnished. 18

Galt's reply that he could furnish 1500 full suits per week resulted in an

order for 5000 gray jackets and pants, "...or any color you can get

...." 19

On 4 June, Galt was asked if he could supply 50,000 men

from the resources of the city, 20

and the next day he was told to have

"...clothing of every description, jackets, pants, shoes, drawers,

shirts, flannels, socks..."

made up as quickly as possible and sent

to Richmond. At the same time he was told to stop the manufacture of the

recruit clothing since the recruiting service was being discontinued. Once

again, he was told to keep up the manufacture of the 1500 suits per week,

although they were now to include "jackets" instead of the

"tunics" prescribed in the regulations. 21

Unfortunately,

Galt misunderstood his orders. In response to the question of whether he

could supply 50,000 men, he contracted with B.W. Woodlief for 50,000

uniforms. This committed the Quartermaster's Department far beyond

its resources, and on 12 June

Myers responded to word of Galt being ill by replacing him with Major

Isaac T. Winnemore. 22

Winnemore

was told to stop all work on clothing, and to cancel the Woodlief

contract. Therefore, very few, if any, of the uniforms prescribed by the 6

June regulations were produced. Myers' concern was not only with his

budget, but with the quality and price of the New Orleans product and with

the unauthorized contract with Woodlief.23

More important, Myers was

increasingly faced with the need to provide clothing on a far larger

scale than had been envisioned or provided by law. On 5 June he had told

Galt:

"...

the

mean description of cloth that the volunteers have been provided with is

almost entirely worn out, and in a few weeks they will be destitute of

most of the articles of clothing. The law requires volunteers to furnish

themselves but as they cannot do so in the field, we must look after their

comfort in this respect..." 24

What

Myers was announcing to Galt was nothing less than a radical new element

in the Quartermaster mission. Whereas by law the Department was

responsible only for clothing the roughly 6000 regulars, now it was taking

on the open-ended responsibility of supplying some of the 100,000

volunteers as well. By mid-July, the new policy was in effect, with

Congressional sanction, and the Department was beginning to supply those

volunteer troops in need, the most destitute being supplied first. 25

A

letter to Captain J.A. Johnston at Norfolk explained the new system:

"...if

the Captains of Companies can make an arrangement to obtain clothing to

be paid for out of the $21 due for the next six months, after the Commutation

has been paid for the first six months, it would be better than to issue

Government clothing to the Volunteers. If that cannot be done such

articles of Clothing as are absolutely necessary may be issued to the

Captains of Companies for their men, with instructions that the value of

the Clothing is to be charged and deducted from the $21 allowed for the

next six months..." 26

Despite

the Department's good intentions, however, it was still only issuing

clothing to needy volunteers, and then only when it had it In response to

his requests for clothing, General John B. Floyd was told that the law

required volunteers to supply themselves, but when the government had

clothing it was issued. At that time (July, 1861) the supply on hand was

not sufficient to fill his requisition 27

By

6 September, a Clothing Bureau had been set up in Richmond to manufacture

clothing, one of several that would eventually supply the armies across

the Confederacy. 28

This Clothing Bureau had two branches: the Shoe

Manufactory under Captain Stephen Putney and the Clothing Manufactory

under O.F. Weisiger. Weisiger, a former Richmond dry goods merchant, ran

the Manufactory as a civilian until he was commissioned a Quartermaster

Captain in 1863. 29

Other

manufactories were eventually established in Nashville, Tennessee;

Athens, Atlanta and Columbus, Georgia; Montgomery, Tuscaloosa and Marion,

Alabama; Jackson and Enterprise, Mississippi; Shreveport, Louisiana and

elsewhere. Not all of the manufactories operated throughout the war, and

by the latter half of the conflict the major centers were in Richmond,

Athens, Atlanta and Columbus. 30

These

Clothing Bureaus operated in much the same way as the U.S. Army's

Schuylkill Arsenal. A limited number of tailors in each manufactory cut

out the pieces of each uniform. The pieces were bundled, and with the

necessary trim, buttons and thread, were issued to seamstresses who sewed

them together and were paid by the completed piece.

A

typical operation was that at Atlanta. In April, 1863 it employed a total

of twenty‑seven men in‑house: a Superintendent, two clerks,

two inspectors, two trimmers and twenty tailors. These men cut and

packaged the uniform pieces, while about 3,000 seamstresses in Atlanta did

the actual sewing in their homes. With this force, the Atlanta operation

manufactured, in the three months ending 31 December 1862:

37,150

Jackets

13,430 Pairs of Pants

13,700 Cotton Drawers

10,475 Cotton Shirts

500 Flannel Shirts

Projections

for the next year (March 1863‑April 1864), if the material could

continue to be supplied, were:

130,000

Jackets

130,000 Pants

175,000 Pairs of Drawers

175,000 Cotton Shirts

130,000 Shoes 31

The

Richmond Manufactory was similar in size and scope, as were Athens and

Columbus. Quartermasters contracted with various mills for finished woolen

and cotton goods, in many cases supplying the raw material. 32

At

the same time, agents were dispatched overseas to procure

materials, and in some cases finished products. Major J.B. Ferguson, who

had been a purchasing agent for the Confederacy early in the war, was sent

to England in September, 1862 as the official Quartermaster purchasing

agent there. He took over procurement of Quartermaster material from Major

Caleb Huse, the Ordnance agent. These efforts began to yield large

quantities of English Army shoes in 1863 as well as bulk woolen cloth.

Although a good deal of this material was received in 1863, by 1864 the

quantities were truly staggering. 33

On

10 June 1864, Captain Weisiger received 4574 yards of English gray cloth,

followed by 4983 more yards on 13 June and 2983 yards of blue English

cloth on 16 June. During the same period he logged in 8425 yards of

domestic woolen goods from four different manufacturers, for a total of

20,966 yards received in one week. This was a rather typical week, and

although there were periods of lesser amounts, the overall volume remained

roughly the same until the end of the war. 34

At

the same time, a number of contracts were let with speculators for

uniforms and cloth to be run through the blockade. Perhap the biggest of

these was let on 12 January 1864 with Haiman and Brother and David

Rosenburg of Columbus, Georgia, for 100,000 uniforms. Delivery was to be

in Liverpool, England in three

batches, due on 1 May, l July and 1 October 1864. Initially to be procured

in Prussia, the contract was later amended to allow purchase anywhere in

Europe and extending the initial delivery date to 1 July and termination

to 1 November 1864. A large portion of the contract had been received by

July, 1864. 35

In

addition to central government operations, the states procured

considerable quantities of clothing. In many cases these items came from

Ladies Aid Societies, 36

but

several of the states, notably Georgia and North Carolina, ran their own

Quartermaster operations similar to those of the central government. In

the case of the latter two states, the Confederate Quartermaster's

Department made loose agreements that those states would continue to

supply their own troops, with the overage going for general distribution. 37

Longstreet's Corps, for example, received 14,000 uniforms from the

state of North Carolina during the winter of 1863-64 38

By

8 October 1862, the issue system was considered to be strong enough that

the old commutation system was officially ended.

39

Some

troops, of course, had been on the issue system as early as the summer of

1861, while others did not get on it until late 1862 or early 1863. There

is evidence that some troops in the west did not get off the commutation

system until 1864 40

Still, in the main armies, the issue system was

pretty much in place and functioning by 1863.

The

issue system provided a table of allowances for specific types of

clothing as well as prices that were to be charged for that clothing. If

the soldier underdrew the allowance, he was paid the difference. If he

overdrew, the difference was taken out of his pay. Prices gradually crept

upward as the war went on, but the basic allowance and prices as of

October, 1862 were as follows:

CLOTHING ALLOWANCE FOR FOR

THREE YEARS 41

| Clothing

Cap,

complete

Cover

Jacket

Trousers

Shirt

Drawers

Shoes, pairs

Socks, pairs

Leather stock

Great-coat

Stable-frock (mounted)

Fatigue overall

Blanket |

1st

2

1

2

3

3

3

4

4

1

1

1

1

1 |

2nd

1

1

1

2

3

2

4

4

0

0

1

0

0 |

3rd

1

1

1

2

3

2

4

4

0

0

1

1

1 |

Price

$2.00

.38

12.00

9.00

3.00

3.00

6.00

1.00

.25

25.00

2.00

3.00

7.50 |

It

was under this system, with clothing supplied primarily by the various

clothing manufactories, and supplemented by state issues, contract

clothing and foreign imports, that the Confederate soldier was supplied.

Of course, captured Federal clothing and items supplied by the soldiers'

families also played apart, but the extent of it is hard to gauge, because

this clothing generally does not appear on the official issue records,

or when it is, is not delineated as such. 42

The

important thing to keep in mind about the Clothing Manufactories is that,

in common with the decentralized nature of the war and the overall

Confederate policy of each army supplying itself from its own departmental

resources,

the products of each depot varied depending on local resources. The

patterns of the uniforms themselves also varied. Despite the fact that the

Regulations called for "tunics" in 1861 and "frock

coats" thereafter, the uniform prescribed by the 1862 issue system

was the "jacket." There is no evidence that any of the central

government depots produced frock coats in any numbers, although apparently

some of the state operations did. 43

More

importantly, at no time did the Quartermaster General detail to any of

the depots exactly how the jackets were to be made. Thus, materials, cut,

number of buttons, pockets and the presence or absence of trim were

determined by each depot on its own, and probably changed as circumstances

dictated.

Materials

used could vary depending on what was available at any given time. The

Richmond manufactory, for example, dealt mainly with four textile mills. 44

Of these, the Crenshaw Woolen Mills of Richmond was capable of producing

all-wool material as well as woolen goods on a cotton warp. 45

Kelly,

Tackett & Ford of Manchester, Virginia produced a variety, including

red flannel and some sky blue cloth. 46

Bonsack & Whitmore of Bonsack's

Depot, Virginia also produced only woolen jeans while the Scottsville Manufacturing

Company of Scottsville, Virginia apparently did the same.47

In addition,

the Richmond Depot also received a considerable quantity of imported

English cloth. Lining material was almost entirely unbleached cotton

osnaburg, produced mainly by the Matoaca Manufacturing Company, the

Battersea Mills and the Ettrick Manufacturing Company. These mills also

produced shirting. 48

Despite the variety of materials, the patterns used

for cutting the garments appear to have remained consistent over time.

What

was true for Richmond was true for the other depots as well. Therefore, if

today we find a group of uniforms with histories that indicate issue to a

given army, and if those uniforms are consistent in cut, if not always in

materials, they can usually be attributed to the main depot supplying the

army.

Following

are some tentative attributions of various uniform types to certain of the

Quartermaster Depots. The term "tentative" must be emphasized

here, for in over fifteen years of research and the examination of nearly

150 original Confederate enlisted men's uniforms, not one has yet been

found with a depot marking, and none of those produced domestically even

have a size mark.

Two

basic rules of thumb in these attributions have been that there must be at

least three surviving uniforms of a given type to constitute a pattern,

and those uniforms should each have histories that indicate a common

source. Moreover, if a uniform survives today and if the soldier who wore

it was still in service in 1865, and unless there is evidence to the

contrary, the uniform is considered to be the last one he was issued.

This

article was originally published in the Fall and Winter 1989 issues of The

Military Collector & Historian.

©

Copyright 1989 Company of Military Historians.

Journal page.

NOTES

|

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

|

The basic starting point in the material culture of this period is

Frederick P. Todd, Lee A. Wallace, George Woodbridge and Michael J.McAfee,

American Military Equipage,

1851-1872 (Providence, 1974,

1977, 1978 and Privately Printed, 1978).

A good broad brush approach to the Confederate supply system is John

D. Goff, Confederate Supply (Durham,

1969), while a good study of

Quartermaster operations in one department is James L. Nichols, The Confederate

Quartermaster in the

Trans-Mississippi, (Austin, 1964).

Foreign operations are covered in Samuel Bernard Thompson, Confederate

Purchasing Operations Abroad, (Chapel

Hill, 1935) and Richard C. Todd,

Confederate Finance, (Athens, 1954).

None of these studies, however, have dealt with the Clothing Bureaus

in enough detail to determine uniform types.

In particular, see MUIA plates 10, 99,

107, 127, 146, 151, 163, 176,

198, 219, and 236,

all of which depict early war Confederate units. See also Frederick P.

Todd, "Notes on the Organization and Uniforms of South Carolina

Military Forces, 1860-1861,"MC&H,

III:

53‑62 and Lee A.

Wallace, Jr. "The Volunteers of the Second Brigade, Fourth

Division," Pan I, MC&H, X:

61‑70; Part 11, MC&H,

X 95-101; Part III,

MC&H,

XI: 70-79.

See, for example,

Part V of William A. Albaugh III and Edward

N. Simmons, Confederate Arms (Harrisburg,

1957).

A full list of the sources that support this theme would be

impossible to list, but the basic concept is reiterated in article after

article in Confederate

Veteran magazine, as well as other veteran's publications,

reminiscences and United Daughter of the Confederacy publications. More

important, a strong oral tradition exists in this area.

The same legend

building that applied to Robert E. Lee applied to the Confederacy as a

whole. See Thomas L. Connelly, The Marble Man,

Robert E. Lee and His Image in

American Society (New York, 1977)

for a discussion of the processes and some of the individuals

involved.

W.W. Blackford, War Years

With J.E.B. Stuart (New York, 1945),

p. 99.

"Resources of the Confederacy in February, 1865,"

Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 11, No. 3,

September, 1876,

pp.117‑120.

Walter H. Taylor, Four

Years With General Lee (Reprint, New York,

1962), p. 183.

Special Order No. 57, 3 October

1864, Order Book, Corse's Brigade, Picken's Division, AXV.,

Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library,

Museum

of the Confederacy, Richmond, VA.

Ibid., Special Order No. 7, 18 February, 1865.

"Resources of the Confederacy..." S.H.S.P., B, 3,

p.120.

"An Act for the Establishment and Organization of a

General Staff for the Army of the Confederate States, 26

February, 1861. War of the

Rebellion, The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (GPO,

Washington), IV, 1, p.114, cited

hereafter as O.R.; "An Act

for the Establishment and Organization of the Army of the Confederate

States of America:' 6 March 1861, The Statutes at Large of the Provisional Government of the

Confederate States of America, from the Institution of the Government,

February 8,1861, to its Termination, February 18,1862, Inclusive. (Richmond,

1864), pp. 5462 "An Act

Amendatory of an Act for the Organization of the Staff Departments of the

Army and an Act for the Establishment and Organization of the Staff of the

Army of the Confederate States, 14 March,

1861, O.R., IV, 1, p. 163.

"An Act to Provide for the Public Defense," 6 March, 1861, Statutes,

pp. 45‑46.

O.R., IV, I, p. 126.

A.C. Myers to Captain

J.M. Gale, 19

April, 1861 in Letters

and

elegrams Sent, Confederate

Quartermaster General's Office, Na

tional Archives (cited hereafter as NA), RG 109,

Chapter V, Cited

hereafter as Letters Sent,

CSQMG.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 19 April

1861.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 24 May

1861.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 31 May

1861.

Galt to Myers, 31 May

1861 in Register

of Letters Received, Confedrate Quartermaster General's Office, NA,

Chap. 5, Vol. 1, and Myers to Galt, 3 June 1861,

Letters Sent, CSQMG.

Myers to Galt, 4 June 1861,

Letters Sent, CSQMG.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 5 June

1861.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 12 June

1861; Myers to Winnemore, 12

June 1861.

Ibid., Myers to Galt, 19 June

1861; Myers to Winnemore, 21 June, 24

June, 27 June 1861.

Ibid., Meyers to Galt, 5 June

1861.

Ibid., Myers to Lt. John R. Cooke,

AAQM, 5 July 1861;

Myers to LTC W. L. Cabell, Chief Quartermaster, Army of the Potomac, 9

July

1861.

Ibid., Myers to Capt.

J.A. Johnston, 19 July 1861.

Ibid., Myers to Gen. John B. Floyd, 20 July

1861.

Ibid., Myers to

T.W. Lane, Esq., Glennville, AL, 6

September 1861.

NA, Compiled Service Records, Major Richard P. Waller, Captain

O.F. Weisiger, Compiled

Service Records of General and Staff

Officers

and Non Regimental Enlisted Men,

cited hereafter as CSR.

Gaff, pp. 70-71.

OR. I, XXIII, 2, pp. 766‑769.

Shipping Book, Richmond

Clothing Depot, 1863‑1865 NA, RG 109,

Chapter

V, Vol. 218, Cited hereafter as Shipping

Book

Gaff, pp. 68, 144.

Shipping Book.

Contras, 12 January 1864, QMG with David Rosenberg and Lewis

and Elias Haiman, NA, RG 365, Entry 59, Treasury

Dept., Contracts.; NA, RG 109, Chapter V, Vol. 227, QMD Memoranda

Book,

1864.

Numerous letters detailing clothing manufacture by these societies

may be found, for example, in the Alabama Quartermaster's papers

at the Alabama Dept of Archives and History, Montgomery. See also

Circular, from the Quartermaster General of South Carolina to the

Soldiers Aid Societies of South Carolina, Charleston

Mercury, 19

October

1861.

Myers to Gov. Henry T. Clark, 12 June 1862, Letters

Sent, CSQMG; Myers to BG Ira Foster, QMG, State of Georgia, 12

November 1863, Georgia

Division of Archives and History.

"Address of Governor Zebulon Vance to the Association of the

Maryland Line," in Walter Clark, North

Carolina Regiments, Vol. I,p. 35.

G.O. 100, Adjutant & Inspector General's Office (A8cIG0), 6

December 1862.

Letter, Dan Brown, Historian,

Kenesaw National Battlefield Park to

author, 1978.

G.O. 100,

ABr.IGO, 6 December 1862.

An exception is in CSR, Adrian, James F., Co. F, 48th Alabama

Infantry, requisition dated 30 June 1863. Among 24 trousers is

"1 captured."

Advertisement, HQ South Carolina Militia, 15 February 1861.

Charleston Mercury, 20 February 1861. Several single breasted

frock coats for enlisted men exist with histories of belonging to

Georgia state soldiers during the Atlanta campaign.

Abstracts of Articles

Purchased, Received, Issued, Sold, Lost and

Expended

by Captain Richard P. Waller, Assistant Quartermaster at

Richmond, 1861-62. NA,

RG 109, Chapter V, Vol. 244.

Crenshaw & Co., Richmond, VA, NA, RG 109, Confederate

Papers

Relating to Citizens or Business

Firms, cited hereafter as CBF.

Kelly, Tackett & Ford, Manchester, VA, RG 109, CBF.

Bonsack & Whitmore, Bonsack's Depot, VA, CBF.

Scottsville Woolen Mills, Scottsville, VA. CBF.

Shipping Book.

|